THE NORTHEAST REGION AND THE CLIMATE CHALLENGE

The Northeast Region, as defined by the USGS for its DOI Regional Climate Science Center, is a region of enormous diversity in geography, climate, biological diversity, and human land use. The Northeast region contains 22 states, multiple ecoregions, seven of the 21 regions established for the National Landscape Conservation Cooperative (LCC) Program, and a human population of 131,000,000 (41% of the US population). Consequently, the Northeast region poses many unique challenges for understanding, adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change.

FOURTH NATIONAL CLIMATE ASSESSMENT - KEY MESSAGES FOR NORTHEAST AND MIDWEST REGIONS

NOTE: In 2018 the National Climate Assessment the regions are referred to as the Northeast and Midwest. Both of these identified regions fall within the the DOI Northeast Climate Science Center region. The following are excerpts from the NCA 4 with links to the chapters for further information.

The Fourth National Climate Assessment presents five key messages for the Northwest region and six key messages for the Midwest region. Click on the boxes below to see each key message in its entirety.

NORTHEAST KEY MESSAGES

Changing Seasons Affect Rural Ecosystems, Environments, and Economies

The seasonality of the Northeast is central to the region’s sense of place and is an important driver of rural economies. Less distinct seasons with milder winter and earlier spring conditions are already altering ecosystems and environments in ways that adversely impact tourism, farming, and forestry. The region’s rural industries and livelihoods are at risk from further changes to forests, wildlife, snowpack, and streamflow.

Changing Coastal and Ocean Habitats, Ecosystem Services, and Livelihoods

The Northeast’s coast and ocean support commerce, tourism, and recreation that are important to the region’s economy and way of life. Warmer ocean temperatures, sea level rise, and ocean acidification threaten these services. The adaptive capacity of marine ecosystems and coastal communities will influence ecological and socioeconomic outcomes as climate risks increase.

Maintaining Urban Areas and Communities and Their Interconnectedness

The Northeast’s urban centers and their interconnections are regional and national hubs for cultural and economic activity. Major negative impacts on critical infrastructure, urban economies, and nationally significant historic sites are already occurring and will become more common with a changing climate.

Threats to Human Health

Changing climate threatens the health and well-being of people in the Northeast through more extreme weather, warmer temperatures, degradation of air and water quality, and sea level rise. These environmental changes are expected to lead to health-related impacts and costs, including additional deaths, emergency room visits and hospitalizations, and a lower quality of life. Health impacts are expected to vary by location, age, current health, and other characteristics of individuals and communities.

Adaptation to Climate Change Is Underway

Communities in the Northeast are proactively planning and implementing actions to reduce risks posed by climate change. Using decision support tools to develop and apply adaptation strategies informs both the value of adopting solutions and the remaining challenges. Experience since the last assessment provides a foundation to advance future adaptation efforts.

MIDWEST KEY MESSAGES

Agriculture

The Midwest is a major producer of a wide range of food and animal feed for national consumption and international trade. Increases in warm-season absolute humidity and precipitation have eroded soils, created favorable conditions for pests and pathogens, and degraded the quality of stored grain. Projected changes in precipitation, coupled with rising extreme temperatures before mid-century, will reduce Midwest agricultural productivity to levels of the 1980s without major technological advances.

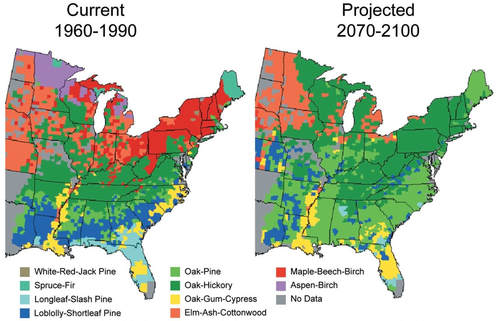

Forestry

Midwest forests provide numerous economic and ecological benefits, yet threats from a changing climate are interacting with existing stressors such as invasive species and pests to increase tree mortality and reduce forest productivity. Without adaptive actions, these interactions will result in the loss of economically and culturally important tree species such as paper birch and black ash and are expected to lead to the conversion of some forests to other forest types or even to non-forested ecosystems by the end of the century. Land managers are beginning to manage risk in forests by increasing diversity and selecting for tree species adapted to a range of projected conditions.

Biodiversity and ecosystems

The ecosystems of the Midwest support a diverse array of native species and provide people with essential services such as water purification, flood control, resource provision, crop pollination, and recreational opportunities. Species and ecosystems, including the important freshwater resources of the Great Lakes, are typically most at risk when climate stressors, like temperature increases, interact with land-use change, habitat loss, pollution, nutrient inputs, and nonnative invasive species. Restoration of natural systems, increases in the use of green infrastructure, and targeted conservation efforts, especially of wetland systems, can help protect people and nature from climate change impacts.

Human Health

Climate change is expected to worsen existing health conditions and introduce new health threats by increasing the frequency and intensity of poor air quality days, extreme high temperature events, and heavy rainfalls; extending pollen seasons; and modifying the distribution of disease-carrying pests and insects. By mid-century, the region is projected to experience substantial, yet avoidable, loss of life, worsened health conditions, and economic impacts estimated in the billions of dollars as a result of these changes. Improved basic health services and increased public health measures—including surveillance and monitoring—can prevent or reduce these impacts.

Transportation and Infrastructure

Climate change is expected to worsen existing health conditions and introduce new health threats by increasing the frequency and intensity of poor air quality days, extreme high temperature events, and heavy rainfalls; extending pollen seasons; and modifying the distribution of disease-carrying pests and insects. By mid-century, the region is projected to experience substantial, yet avoidable, loss of life, worsened health conditions, and economic impacts estimated in the billions of dollars as a result of these changes. Improved basic health services and increased public health measures—including surveillance and monitoring—can prevent or reduce these impacts.

Community Vulnerability and Adaptation

At-risk communities in the Midwest are becoming more vulnerable to climate change impacts such as flooding, drought, and increases in urban heat islands. Tribal nations are especially vulnerable because of their reliance on threatened natural resources for their cultural, subsistence, and economic needs. Integrating climate adaptation into planning processes offers an opportunity to better manage climate risks now. Developing knowledge for decision-making in cooperation with vulnerable communities and tribal nations will help to build adaptive capacity and increase resilience.

PREDICTED IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

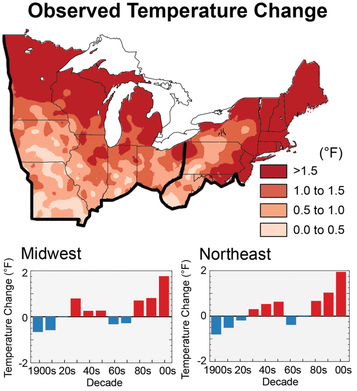

Temperature

- Since 1900, average temperatures have increased by 1.8°F (1°C)

- By 2050, average air temperatures are projected to increase by approximately 2.5°F (1.4°C).

- By 2100, average air temperatures are projected to increase by 3 to 12 °F (1.6 to 6.6°C).

- Warm-season temperatures are projected to increase more in the Midwest than any other region of the United States.

- Winter temperatures have been rising faster than temperatures during other seasons. In the Northeast specifically winters are warming three times faster than summers.

- Freezing days are projected to decline by 10 to 90 days by

2041–70 across North America. - The frost-free season is projected to increase 10 days by early this century (2016–2045), 20 days by mid-century (2036–2065), and possibly a month by late century (2070–2099) compared to the period 1976–2005

Forests

- Changing temperature and precipitation will force many forest ecosystems northward, but many tree species will be unable to migrate fast enough to keep up with the pace of climate change.

- As species fail to keep up with the pace of climate change, forest ecosystems will see declines in biodiversity and overall resiliency.

- Climate change will amplify existing stressors to natural and urban forests.

- Climate change impacts on forests will impair the ability of many forested watersheds to produce reliable supplies of clean water and other forest products.

- Climate change will alter cultural and recreational connections to forest ecosystems.

Precipitation

- The frequency and intensity of severe storms has increased. This trend will likely continue as the effects of climate change become more pronounced.

- The amount of precipitation falling in the heaviest 1% of storms increased by 37% in the Midwest and 71% in the Northeast from 1958 to 2012.

- Heavier storms are projected to increase in frequency at a faster rate than storms that are less intense.

- The amount of precipitation falling during intense multi-day events has increased dramatically

- Increased spring precipitation and higher temperatures and humidity are expected to increase the number and intensity of fungus and disease outbreaks and the prevalence of bacterial plant diseases, such as bacterial spot in pumpkin and squash. Increased precipitation and soil moisture in a warmer climate also lead to increased loss of soil carbon and degraded surface water quality due to loss of soil particles and nutrients. Transitions from extremes of drought to floods, in particular, increase nitrogen levels in rivers and lead to harmful algal blooms.

- Climate change modeling suggests that the southern half of the Midwest likely will see increases in saturated soils, which also indicates risks to agriculture and property from inundation and flooding; recent work incorporating land-use change and population changes also suggests the number of people at risk from flooding will increase across much of the Midwest.

- Because infrastructure was not designed with current precipitation trends in mind, storm drain and sewage systems in both the Midwest and Northeast are already experiencing increasing incidents of issues such as back-ups and flooding during heavy precipitation events, which can cause structural damage and present health risks.